The

Neandering Mind

This is completely speculative, we know Neanderthals had

brains and must have had a mind...but was there a difference between

their mental experience and ours? Axiomatically we are cut off from

their inner life, but archaeologically we can parse out similarities.

In the large scale evolutionary history of our genus, the personality

traits of a Neanderthal and the personality traits of a modern human

are two variations on a similar theme. We both experienced

experience, an inner life exists for us as much as it existed for a

Neanderthal. While definitively proving the existence of the

Neanderthal mind is impossible at the moment, the fossil record can

be used to infer important details. Analyzing specific circumstances

of a Neanderthal's life can give us certain actions and happenstances

which their mind had to encounter. Examining the physical life of a

Neanderthal can show us what their mind had to overcome to survive,

and possibly can show what their mind considered and thought about.

Pragmatism,

Stoicism, and Bravery

“[Neanderthals had] tenacity, or dogged

persistence. Neanderthals must have been able to complete their tasks

while in pain or with diminished capacity.” -Thomas Wynn,

Frederick Collidge. Crippled Neanderthals would live and thrive years

after grievous injuries, and many would have to shrug off pain and

discomfort to survive day by day. Neanderthals share this trait with

their predecessors and ourselves, yet Neanderthal bones show more

damage than our bones. Erik Trinkaus conducted a study to see if

there was any correlation between Neanderthal bone damage and modern

human bone damage. This would determine which modern behavior creates

similar fractures. As it turns out, modern rodeo cowboys suffer the

same level and types of damage as Neanderthals. Neanderthal life

consisted of getting up close and personal with large animals, often

resulting in injury or death. “Neanderthals had the ability to

withstand the pain, discomfort, fatigue, and hunger that were part of

their everyday existence...Death was a constant companion;

Neanderthals faced their mortality every day...Neanderthals had a

concept of death, and...it was clearly something that they thought

about.” -Thomas Wynn, Frederick Collidge.

Related to pragmatism is the way Neanderthals treated a

body after death. While some groups practiced burial including the

building of monuments and rituals, others did not, and some simply

pushed the bones away from their living space. While Neanderthals

would have affection for a living member of their clan, once that

member died some groups of Neanderthals lost their sentimentality.

There is much evidence of nutritional cannibalism in Neanderthal

culture, either of other groups or of their own group. Changing the

way you treat a body, from an individual, to a source of food, is

purely pragmatic and speaks to the utility of the Neanderthal mind.

At Moula-Guercy cave a group of Neanderthals came upon another clan

and killed 6 of their members, dismembering and eating them

afterward. They cracked open their skulls to eat their brains, cut

the meat off their bones and crushed them for the marrow, and cut out

their tongues. This is the same practice that Neanderthals would have

done to butcher their common food source, red deer. Treating another

Neanderthal body in such a way is completely pragmatic, dependent

entirely on the lack of food and the necessity of your group over

another. This is indicative of the way a Neanderthal mind would have

looked at the world, while developed enough to feel compassion for a

relative, pragmatic enough to butcher another tribe's children for

food. At the time, we shared this frightening sense of practicality,

contemporaneous humans were just as cannibalistic. Even today, while

we may not eat another tribe's children, we still kill them without

mercy.

Pragmatism also covers the practical necessities of

group living. Neanderthals, like the rest of our genus, relied on

forms of grooming for social cohesion. With the development of

complex language and abstract thought our genus was able to use

absurdity, juxtaposition, and the exploitation of surprise, to

tell a joke. The question is, when did this capacity develop? The

evolutionary necessity for joke-telling increases as group population

size increases. Once your tribe is larger than your immediate family

(socially bonded by love), then an individual has to find another way

to make connections. Since Neanderthal clans were only made up of

their immediate family, it is possible that they did not share the

need for complex social growth that their human neighbors did.

Neanderthals may not have had the mental acuity to craft a joke, the

ability to juxtapose seeming incoherent objects may have been outside

of their mental reach, “they lacked either the motivation or the

ability to make others laugh...” -Thomas Wynn, Frederick

Collidge. While the abstraction and incoherent strangeness of human

jokes may have been outside of their purview, absurdity through

tomfoolery very much was a part of their life. The development of

slap-stick comedy goes back to our chimpanzee ancestors, and

certainly Neanderthals exploited this form of social bonding, “they

may have had clowns who would make others laugh.” -Thomas Wynn,

Frederick Collidge.

Another practical problem of social life is genetic

diversity. While not consciously an issue, it was certainly overcome

since those Neanderthal clans who continued their lineage within the

family died out due to inbreeding. All species in our genus and

further back practice some form of out-migration. This is when a

child leaves the group and travels to join another group, usually

this practice is given a cultural reason but practically it helps

spread the flow of genes. Usually the culture chooses who leaves the

group, sometimes it is always male and other times always female. At

one Neanderthal site, all the males in a clan were related, evidence

that the migrants were female. Yet at many human hunter-gatherer

sites, the females and especially grandmothers supply the most food

from their local plant knowledge. Many societies which rely on the

knowledge of females practice male out-migration. While it is not

known whether Neanderthals practiced male or female out-migration,

they most likely chose one – humans are the only species in our

genus in which local culture selects the gender of the migrant, and

some human cultures out-migrate both genders. Thomas Wynn and

Frederick Collidge suggest that the practice of Neanderthal trading

may not have been similar to human trading at all. Neanderthals may

have given a precious stone to the out-migrating child, so as to ease

the transition from one clan to another through gift giving.

“Neanderthals relied on families and the emotion bonds that bound them together. There was no need for cheater detection, which became advantageous only when non-emotional and contract-like agreements between acquaintances and even strangers became common...We suspect that Neanderthals' direct, emotional, embodied style of social cognition placed them at a marked disadvantage...The modern humans who entered...Europe...lived in larger face-to-face groups than Neanderthals did, maintained regular social contracts with acquaintances who lived hundreds of kilometers away, and almost certainly had the ability to negotiate with strangers, Neanderthals would not have known how to respond.” -Thomas Wynn, Frederick Collidge

While

Thomas Wynn and Frederick Collidge put forth an interesting argument,

it is times like these where the issue of what exactly constitutes

the Neanderthal mind comes to a head. It is true, Neanderthals

probably did not have the extreme level of social complexity which

characterizes early human groups. That style of interaction is an

evolution of a uniquely human social pressure to form bonds between

large semi-related tribes. Although, to say that Neanderthals

completely lacked some mental ability (such as the ability to detect

cheaters) is going a step further. Simply because humans did it

better does not mean that Neanderthals did not do it at all.

|

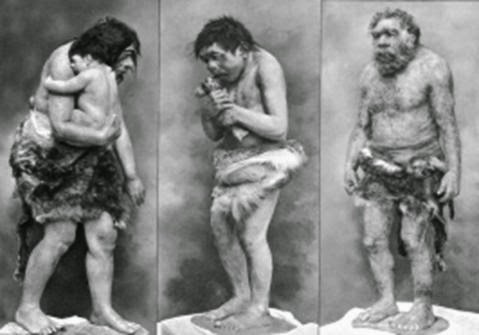

| A reconstruction of the La Chapelle-aux-Saints Neanderthal, by the Field Museum of Natural History at Chicago |

Since

items were traded hundreds of miles through multiple clan's

territories, there must have been some form of cheater detection. How

could a Neanderthal understand the idea behind a trade without the

requisite idea of being cheated? If one clan traded with another,

then there was some form of a contract-like agreement, the ability to

trade requires interacting with strangers in a level-headed and

balanced manner. Besides trading, if Neanderthals did not do this,

how did we end up breeding with them at all? Neanderthal

out-migrating children would have been strangers to their new

families, and Neanderthals had an institutionalized response to these

newcomers (letting them stay). If Neanderthals “would not

have known how to respond” how

did their genetic pool stay diverse and healthy?

|

| A reconstruction of the La Chapelle-aux-Saints Neanderthal in profile, by the Field Museum of Natural History at Chicago |

Sometimes

multiple clans would gather at a site for a grand feast, these clans

were sometimes distantly related, and sometimes knew each other.

Other times, they would not have been related, and would not have

known each other. Yet at these sites clans cooperatively butchered

large animals or hundreds of smaller game, divvying up the spoils

without widespread violence then organizing the remains into

specified piles. All of these actions require a significant amount of

stranger and acquaintance interaction, including the possibility of

cheating and being cheated. But these obstacles were overcome by

Neanderthals, and multi-clan gatherings are not localized in any one

area but are spread across the Neanderthal range. This is evidence

that their cooperative capacity was not an isolated cultural tactic

but was uniformly spread across their species.

Sympathy

Neanderthal

bones tell us amazing stories of personal hardship and love. Crippled

and paralyzed Neanderthals were given food by their family, and older

members without teeth had their food chewed for them. It is

impossible to understand why a Neanderthal would do such a thing

without recognizing that they felt sympathy. Neanderthal families

structurally operated in the same manner that some humans still do

today, multiple generations living under the same roof all providing

and caring for each other. “With a high mortality rate

and few survivors past the age of forty, Neanderthal families

extended to no more than three generations.” -Thomas

Wynn, Frederick Collidge. The reasons why Neanderthals did this are

twofold: Neanderthals loved and cared for their parents and

grandparents, and Neanderthals relied on the localized knowledge

which older generations had acquired. The first reason is

spontaneous, and we can get a glimpse into how this felt simply by

asking ourselves how does it feel to us now?

While a Neanderthal's experience of love and affection was probably

different in some capacity than ours, it was more similar to our

experience than dissimilar. Human children love their parents, and

human parents love their children – this evolutionary emotional

connection held the same strength in a Neanderthal family as it does

still now in human families (possibly it was felt by Homo

Erectus as well). The daily

struggle for survival which typified the Neanderthal existence put

the same evolutionary pressures on practical teachable knowledge

which still exist in human societies today. The knowledge of which

fauna and flora were edible and which were dangerous was passed down

from generation to generation, and probably went hand-in-hand with

the knowledge of the Levallois technique and clothing creation. The

ability for an elder to teach a child gives the entire species the

capacity to inherit the knowledge of a single individual even after

their death, this is an extreme evolutionary advantage.

|

| Neanderthal facial models by the Senckenberg Institute of Natural History Collections, in Dresden Germany |

It

is remarkable that a Neanderthal would feed a parent who cannot feed

themselves, if only because it seems so genuinely human. We can

immediately relate to the experience of a Neanderthal in that

position, the extreme hardship which humans go through to care for

their aging parents was similarly experienced by a Neanderthal. The

adult Neanderthals had to not only provide food for their children,

but sometimes for their elders as well. Both Neanderthals then and

humans now still haven't come up with a real solution to the problem

of middle aged resource stress (unless you count nursing homes, which

you shouldn't and you should feel bad for considering it). If

Neanderthals cared so deeply for their family members while alive, it

does not seem improbable that they would have grieved in their death.

The construction of tombs and monuments shows that fond memories of a

loved one continued on into the minds of the living, far after ones

death. The construction of a place to go to which represents the

deceased is also a strong indication of the emotion of nostalgia and

emotional process of closure.

“They formed emotional bonds with family and band mates. Someone nursed Shanidar 1 back to health, and someone strived for weeks to keep Shanidar 3 alive, to no avail. Given the harsh conditions of Neanderthal life, this is evidence of a strong emotional attachment.” -Thomas Wynn, Frederick Collidge.

While

complex story driven jokes may not have been in the purview of the

Neanderthal comedic routine, that is not to say that comedy didn't

exist in their society. Neanderthals, as with humans and all our

ancestors, play. This

often includes doing silly or absurd things, and physical comedy.

While certainly Neanderthal children would have played in this

manner, it is possible that adults too shared in comedy. Neanderthals

physically could laugh and smile, and must have laughed and

smiled at something. Exactly

what they found funny or how they amused themselves is impossible to

say, but all hominins including our ancestors did find something

funny. The act of being silly around others usually indicates social

bonding, comfort, and closeness. Neanderthals loved each other, and

probably showed it in the same ways that we still do today.

“Neanderthals very probably could smile and laugh, and it probably happened when they were tickling each other, teasing, or playing. In fact chimpanzees laugh when they are tickled in the same places as humans, so Neanderthals probably laughed when tickled in their armpits and on their bellies and the bottoms of their feet.” -Thomas Wynn, Frederick Collidge.

Callousness

There

are many examples of Neanderthals surviving upper body injuries, yet

very few and practically no examples of surviving lower body

injuries. This seems like an anomaly, since Neanderthals certainly

would have acquired lower body injuries or amputations in combat with

animals or in accidents. The Neanderthal fossil record shows that

while an injured arm was nursed back to health, and injured foot was

not. What exactly does this mean? What we know is that Neanderthals

who did have lower body injuries were not brought back to camp and

buried as others were. What would cause such an anomaly within the

fossil record? Why were some Neanderthals nursed back to health and

others were not? Thomas Wynn and Frederick Collidge suggest that

Neanderthals probably thought along the lines of if you

could not move with the tribe, then you were not cared for.

Neanderthals who were injured in the field away from camp were either

left there to die or were killed outright. When examined without

context this practice seems exceptionally brutal and callous...if a

Neanderthal had the tenacity to feed their aging parent for years why

would they not care for one with a broken leg? It is possible that

Neanderthals recognized that certain injuries were not treatable, and

killed injured family members in a kind of mercy killing. For any

human and for any Neanderthal

this would have been a gut-wrenching decision and the phenomenon

speaks more to their emotion of sympathy than to callousness. Even

then, in the fossil record there is a lack of any attempts

to care for lower body injures,

even minor ones.

Either Neanderthals ignorantly assumed that all lower body injuries

were untreatable, or they callously executed family members for even

minor foot or leg injuries. Both of these options seem unreasonably

strange and foreign to us now, but within the context of their harsh

existence it may have seemed like the reasonable thing to do. It is

always possible that we will eventually discover burials with leg

injures...but for the moment this strange blip in the burial record

can only be explained through ignorance or callousness.

While

Neanderthals loved their family,

they were very willing

to kill another's. While the archeological record contains evidence

of large scale cooperative groups, the constant daily struggle of one

clan against another has been rendered invisible. Yet this invisible

inter-clan warfare was an inseparable part of a Neanderthal's life.

While Neanderthal clans did not trade and interact with each other to

the same degree as early human groups, these clans still fought over

limited resources. Neanderthals certainly experienced interpersonal

violence. The invention of the spear signals both the birth of big

game hunting and the birth of warfare. While the evolution of large

groups helped create the complex social web we live in today, it also

allowed for a novel social interaction...war. Groups kill

other groups, it sounds obvious

but to understand a Neanderthal mind you have to understand this

constant companion, and how strongly it was tied to their lifestyle.

My clan is my family, my group...and your clan are outsiders, my

enemies. This is another emotion with which we can sympathize, since

we still do this all the time.

Humans teach themselves to kill outsiders by removing any and all

personal context from individuals. Once a member of different group

is no longer a self-similar

individual, but one part of a uniform blob of hostile intentions,

they can be killed with little (at the time) damage to our sense of

conscientiousness.

We

have invented astounding ways around this problem of

de-individuation. We actively insert other people's personal context

into our daily lives. We can read about other people around the world

simply by turning on the television, opening a newspaper, or going

anywhere on the

internet. The telephone allows us to talk to anyone anywhere...and

while cynical philosophers love to tout that it has ruined human

communication, it has also radically changed out definition of the

other. Out-groups are no longer

that tribe over there,

but are speaking directly into your ear. Neanderthals did not have

such extreme social luxury, they never saw outsiders on the newspaper

or spoke to them on the telephone...outsiders were

outsiders were outsiders.

Neanderthals did not even have the complex trading connections that

early humans did, which is a form of society that turns acquaintances

into possible trading partners

and eventually into possible

friends. All of this

evidence points to the fact that while it is easy enough for one

human to kill another now, it would only have been even easier for

one Neanderthal to kill another then. Humans are unique in that we

can feel love and compassion towards someone not in our

family or our tribe, people are

outsiders only until we change our minds.

Neanderthals probably could not do this to the extent that we can.

Their family was their only in-group, everyone else was either a

possible trading partner or someone to fight and kill.

No

Autonoetic Thought

You

might be asking yourself, what in the world is autonoetic

thought? While it may not seem

like a common personality trait and it is certainly not something

which we come across on a daily basis...it is extremely common in

humans. In fact, this trait is universal across all human cultures.

What is this trait then? It is the recognition of an afterlife. All

of us have such a recognition, regardless of our religion or lack

thereof. We all understand that whatever the afterlife turns out to

be, it will be different than the life here and now. Humans have

taken this idea into consideration for quite some time, and this

trait explains why humans around the world give such care to burials.

This trait also explains why every religion includes some form of a

life after life. So did Neanderthals think similar thoughts?

This

question becomes difficult to solve when you want to know how people

feel about the afterlife and you cannot ask them.

The question becomes even more difficult when

you are asking about an entirely different species. The most common

archaeological evidence for this in humans are burials and grave

goods. These phenomena give us an inclination that if we found these

things at Neanderthal sites we could make similar extrapolations.

Although this reasoning seems sound, we cannot absolutely know what

made a Neanderthal build a tomb or construct a tumulus. While those

activities in humans are representative of autonoetic thought, for

other hominins they may only have been a memorial. They may only

represent the once living, being unrelated to any idea of a life

after that. Better evidence (in humans) of autonoetic thought is the

presence of grave goods. Every human culture (until modernity) which

left grave goods were preparing the dead for an afterlife. Yet even

considering grave goods as presence of autonoetic thought is

problematic. For other hominins, it is possible that the objects were

only connected to the individual in life, if they brought memories of

that individual or they were that individual's property. In that

regard, Neanderthal grave goods may not show any thought about the

afterlife as well.

While

Neanderthals did (sometimes) make tombs or tumuli, sometimes they did

not bury their family members at all. Neanderthals sometimes left

grave goods, but when they did they left a couple stone tools or

animal bones, most of the time they left nothing at all. While this

is not direct evidence of any thought about the afterlife, it goes to

show that Neanderthals had an idea about death which stands in stark

contrast to our human notion. While it cannot be proven that

Neanderthals did not have autonoetic thought at all, it was either

not nearly as developed as in humans, or simply not there at all. The

proof of this is found when comparing prehistoric human burials to

the relatively simple Neanderthal graves.

An

adult and two human children from the Gravettian culture were buried

in Sungir Russia around 27 kya. By the time this burial took place, a

sea change had occurred in the hominin mind. Here, we do see examples

of autonoetic thought. One child was wearing leather clothing

decorated with 3,000 beads, wearing a beaded leather cap, a painted

stone pendant necklace, mammoth ivory arm bracelets, a belt with 250

fox teeth, a carved ivory animal pendant, an ivory sculpture of a

mammoth, multiple ivory ornamental disks, and an ivory hunting spear.

The rest of the group had dedicated hundreds of hours to preparing

this one person for burial. While it is still possible that the

ornamentation was simply a possession of the deceased, it is more

likely that their culture had developed an idea of the afterlife.

There is no other mental process which would compel people to spend

so much time making things which would never be used except if they

thought that the deceased would use those items in the afterlife. All

of the ornamentation was preparing the individual for an afterlife,

showing complex abstraction, imagination, and strong autonoetic

thought. Other evidence for this is the fact that this child was

buried with an ivory hunting spear. Ivory itself is brittle and would

break after only one jab, contemporaneous humans did not use ivory

for spears because it was commonly recognized as worse than flint or

bone. Ivory spears are only found in burials.

The ivory spear is worthless for the living, it is pointless to use

in daily life...but it was included.

The most reasonable explanation is that the deceased would have used

it. This is evidence that they had a complex conception of the

afterlife, not only was there hunting here but there was hunting

there too. This is

evidence that their afterlife included anything,

evidence that their afterlife had meaning to them. If you enjoy

hunting in this life, you will have an afterlife in which you enjoy

hunting. This shows that their concept was imbued with meaning and

connected to their culture.

If

Neanderthals did think that an afterlife existed, and if it included

an individual who continued their living journey, its properties

would alien to any human notion of such an afterlife. For

Neanderthals, either grave goods were not transferred to the

individual upon death, or objects were thought to be unnecessary for

the individual in the afterlife. Since both of those ideas are not

found in any human conception of the afterlife, either their idea was

radically foreign to ours or simply they had no autonoetic thought.

The concept of existence after this life is inherently tied to the

human struggle to find meaning in an inherently meaningless world. A

human who was a great hunter in this world, was given weapons so that

they could continue hunting in the next. In the mind of that culture,

hunting was given meaning outside of its necessary context. The

tribe, then is given meaning too, as it is now the group's role in

this life to give the deceased a proper burial and preparation.

Giving a cultural meaning to hunting and to burial uses our ability

to make abstractions to create self worth. It also shows that the

tribe understands what that individual needs in the next life,

showing an abstraction on their theory of mind. If Neanderthals had

no autonoetic thought, they may not have found meaning to stretch

past the life of an individual. That non-demonstrable abstraction

which is the afterlife

may have been, for a Neanderthal, unthinkable.

If

Neanderthals did

experience

autonoetic thought, their conception of it is, for us, unthinkable.

Conservatism,

Xenophobia, and Close-mindedness

At

the setting of the Neanderthal era, during the last few thousand

years in which they lived on earth as genetically separate beings

from ourselves – they invented the Chatelperronian industry. If

recent dating evidence is held up, we could say for sure that

Neanderthals independently thought up bone awls and ivory pendants.

Even if this was the case, the Chatelperronian industry only

stretches through parts of France and Spain and only lasts for a

short period of time. It is a fascinating aberration from the dull

normalcy of Neanderthal

industry. In general, Neanderthals did not experiment.

While Neanderthals did make the leap from Acheulean to Mousterian,

once they reached that level they stagnated. For tens of thousands of

years there was no innovation, no invention.

It is almost inconceivable

that millions of individuals lived for thousands of

generations without changing

nor improving on their

technology. Well of course this is inconceivable for humans...there

is something uniquely Homo Sapiens

in our quest for advancement, in our undying curiosity about

mechanics and generally everything.

Neanderthals probably did not experience the notion of curiosity in

the same way, or at least to the same fervent extent. Neanderthals

strangely did not adopt human technology, even after

contact. Some Neanderthals were

even killed by

atl-atls...yet no Neanderthal thought to use them.

“Neanderthals almost never came up with new ways of doing things. As important as it is to understand how Neanderthals might have innovated, it is important also to remember that they almost never did...This virtual absence is perhaps the single most important difference between Neanderthal technical thinking and ours.” -Thomas Wynn, Frederick Collidge.

Why did Neanderthals not innovate? It is impossible to

pin that lack on any one particular issue. It was most likely a

combination of factors stretching from situational circumstance to

their innate mentality. On one hand, since there were so few

Neanderthals compared to modern humans, the rate of invention was

much lower. New individuals with new ideas were far and few between,

compared to human bands. Even if new ideas entered one clan, how

could they spread? With such small group sizes, a lack of large scale

long distance trading, and possible extreme linguistic

diversity...new ideas may have just petered out. It is possible that

innovation was shunned, and inventions simply died with their

inventors. Neanderthals probably shared a conservative and rigid view

of their world. Their small group sizes and hostility to outsiders go

hand in hand – products of their habits and minds as much as of

their culture and lifestyle. If a clan encountered a new idea, it was

probably rejected outright. A Neanderthal alpha may have valued

tradition and familiarity over the risk of novelty. Compared to early

humans, Neanderthals would be thought of as conservative, xenophobic,

and close minded.

How

would such a world-view become the dominant cultural trait of an

entire species? It has a lot to do with the way one learns.

“It is unlikely that Neanderthal children had more than a

few active adults from whom to learn...a Neanderthal child...learned

from watching a close relative.” -Thomas

Wynn, Frederick Collidge. A Neanderthal child during youth was taught

the Levallois technique of flake production. The child did not

deviate from the technique, did not innovate, but mastered it as

it was taught to them. Once that

child became an adult, the technique was then passed down to another

generation, and so on, for over 100,000 years.

It is difficult to imagine how this could have been done, simply

because humans act so radically different.

Modern human youth is full of ideological plasticity, full of a

constant yearning for the new and untried. While Neanderthal children

may have shared a similar desire for personal betterment, that need

was not fulfilled in the same manner. Youth was not marked by

innovation and creativity, but by the adoption and replication of the

proven techniques of your parents – any derivation from these

proven tactics was seen as imperfect learning as

opposed to inventive creation.

No comments:

Post a Comment