While

we have looked at many aspects of Minoan life during both the OT and

NT periods, we have not looked at life during their cultural decline.

The splendor of the NT period, with its large temples, elaborate

jewelry, and expansive colonies was surely the peak of bronze age

Crete. The Theran eruption heralded a new period, one in which the

labyrinth at Knossos was the sole temple-palace on the island. The

shining jewel in the Minoan crown, Thera, had been utterly

annihilated and abandoned. Knossian dominance might have even allowed

them control of the entire island, but it is unknown. Depending on

the dating of the eruption, Knossian domination was either a brief

period between 1,470-1,380 in the final waning hours of the Minoan

culture, or its most vibrant golden age between 1,600-1,380. Both

pictures paint the city of Knossos as a central facet of the unique

Minoan culture during the LBA, but its stability was in the end an

impossible task. The world around them had changed, and even their

“wooden walls” could not save them.

By

1,400 BCE Minoan pottery began to become rigid and formal, it had

essentially started to become Mycenaean. Specific scenes became

standardized, and copied across the island. The patronage of the

nobility was no longer the source of creativity that it once was.

Cultural novelty still occurred, as the new Knossian Palace Style

pottery proliferated during this period. Palace style and rich

Mycenaean pottery were still made by potters specifically for the

wealthy, and new forms of pots which show distinctive Mycenaean

traits appear in the record. Helmets and shields begin to more

heavily appear on pottery during this period, showing the rising

importance of warfare in art.

|

| Reconstruction of the palace of Knossos, from httpearth-chronicles.runews2013-09-23-51570 |

The

post-1,400 BCE switch in general pottery styles was simultaneous in

an island wide switch to Linear B (and Proto-Greek) from Linear A

(the Minoan language). These pieces of evidence suggest that the

island was conquered by mainland rulers, and its elite was replaced

by ethnic Greeks. On the mainland this period after 1,400 BCE was a

renaissance: instead of a single city's dominance (Knossos), the

mainland was controlled by a series of walled cities ruled by kings.

These kings extended their control into the hinterlands, marrying far

off families to secure political alliances and gave patronage to

local artists be it pottery, metalworking, or fresco painting. Over

the course of 200 years Mycenaean culture and people would usurp the

trading empire of their ideological ancestors throughout the eastern

Mediterranean. While it is impossible to know which Minoan

settlements were destroyed by the Mycenaeans and which weren't, what

is assured is that after 1,400 BCE Mycenaean culture had come to

Crete, and it had come to stay.

The

Great Fire of 1,380, and the 14th Century BCE

The

Knossian period on Crete was brought to an end by a giant fire, which

destroyed the labyrinth at Knossos around 1,380 BCE. While people

continued to live in the town around the gutted labyrinth, the temple

proper was abandoned. Around 1,380 BCE the city of Thebes on the

mainland was also destroyed, this was a perilous time for Mycenaeans

and Minoans alike. After the great fire, the art of elaborate seal

carving began to die out on Crete, and temples were no longer built

on the island. There were many reasons why such an ancient practice

would finally end, most plainly it is an example of the lack of a

strong political will. The building of palace-temples took a king

with good international trading connections, a good supply of stone

and manpower, and more importantly time and stability. These pillars

of megalithic construction were no longer present on the island.

Another

significant factor was a general shortage in materials. By the LM

period most of Crete's native cedar forests had been depleted through

its kings' large construction projects. Palace-temples required large

amounts of wooden rafters, making their construction prohibitively

high for the weaker rulers on Crete post-1,380 BCE. In addition to

large structural changes, larnakes were introduced and became

widespread during this period. A widespread change the method of

burial points to a much larger shift in the Minoan mindset,

considering these beliefs do not change flippantly. These new Minoans

buried their dead differently, they lived in towns near the ruins of

palace-temples, and their kings no longer used scribes (or if they

did it was not on the same scale)...society had changed dramatically.

|

| An aerial picture of the modern day ruins at Knossos |

Minoan

cities no longer built giant palace-temples to calcify their

authority, and their artists no longer dominated the fashion of the

eastern Mediterranean. By 1,300 BCE Linear B was used throughout the

island, as well as Mycenaean pottery, sealings, and artistic styles.

Minoan culture entered a serious decline, and between 1,380-1,100 BCE

settlements across Crete become smaller, walled, and move inland.

These post-temple settlements were designed solely to account for

defense, violence prevailed and the Minoan culture was on the

defensive. With the domination of foreign art and language, and

beleaguered by pirates the Minoans were fighting a losing battle, by

1,000 BCE Minoan material culture had ceased to exist. Some

historians have suggested that the influx of Mycenaean culture on

Crete during this period is from refugees, and not from an invasion,

but either explanation reveals a confusing period rife with

instability.

The

end of the palaces also meant the end of organized religion on Crete,

and after 1,380 BCE the primary cultic focus of many Minoans' lives

had reverted back to their traditional cave cults. Peak sanctuaries

had most died out by this period, but considering cave sanctuaries

are harder for pillagers to find it is sensible that these would

become the dominant areas of stored iconography. The Minoan religion

could not survive foreign influence either, and around 1,200 BCE even

cave cults had died out. Aspects of the Minoan religion and mythology

continued on in the hearts of their worshipers, influencing the

origin story of Cretan Zeus as it was told in the 5th

century BCE.

%2C%2Bby%2BC.%2BDietrich.jpg) |

| Reconstruction of a domestic shrine in house X of the southern area in Kommos, Crete, post palatial period (1,380-1,100 or 1,000 BCE), by C. Dietrich |

The

Trojan War and Sea Peoples, the 13th

Century BCE

|

| “Peoples of the Sea” by Giuseppe Rava |

By

1,300 BCE Mycenaeans had complete control over the Aegean, and by

this period had large established colonies in Cyprus and on the

Anatolian coast (with the centerpiece being the large city of

Miletus). This is the century of Mycenaean hegemony. While

Greco-Roman scholars placed the Trojan War in this period (by

counting successive generations) placing mythical accounts of

Mycenaean warfare in this century was if anything a lucky guess. In

the middle of this century the rulers of Mycenae cemented their power

through massive construction projects, in effect redefining their

city's political and historical narrative. Around 1,250 BCE they

extended the citadel so as to include Grave Circle A. They built a

wall around the Grave Circle, repaired fallen stele dedicated to

ancestral nobles, and built a small shrine at the site. The mid 13th

century rulers of Mycenae intended to connect their current stable

government to the glorious historic kings of 16th century.

The 13th century rulers intended to change the narrative:

those old kings would no longer languish in run-down burials outside

the citadel, but were the venerated ancestral heroes whose ethereal

power now propelled Mycenae's 13th century fortune. The

city's glorious past was connected to their present, but this was not

enough. The huge and imposing Lion Gate was built to crown the main

gate of the city, and current kings were interred in beautiful tombs

like the Treasury of Atreus. On Crete, small settlements moved

further inland to escape sea raids, while on the mainland their

cultural progeny proliferated.

|

| A late Minoan jug, 1,300-1,200 BCE |

%2BIIIB2%2B(1250-1180%2BBCE).jpg) |

| A late Mycenaean figurine, ca. 1,200 BCE |

Around

1,200 BCE there was yet another collapse on Crete, many places were

burned and destroyed. This collapse was most likely caused by waves

of Sea Peoples. After this series of raids, many old Minoan sites

were finally abandoned, being left in obscurity forever. It is

possible that the place name Minoa was

introduced into Gaza around this time by the Peleset tribe (one of

the groups considered Sea Peoples). The Peleset had fought with the

Egyptians, forcing them to concede Gaza for the Peleset's settlement.

The Sea Peoples as a whole may have included Cretans and Mycenaeans,

who would have brought their native place name.

|

| A map of cities destroyed around 1,200 BCE |

|

| A reenactor from the Koryvantes group as a member of the Sherden tribe of Sea Peoples |

Around

1,200 BCE on the mainland the then Wanax of Mycenae built an

underground cistern which would have greatly helped the city survive

a siege. This period was

calamitous for Greeks, around

1,200 BCE there is a general decrease in the number of Mycenaean

sites: 9/10 are lost in Boeotia, and 2/3 are lost in Argolis. It

is the end of the Mycenaean palace culture, and many

Mycenaeans fled to their colonies: to

Cyprus, the Aegean islands,

and to the Anatolian

coast.

“This collapse was not instant and was not total. In addition to the individual sites, there are several elements of continuity; material culture remains mostly the same as before for another century or more (not only continued Mycenaean material culture but Minoan material culture as well), shipbuilding technology, ceramics, and agricultural practices are not disturbed in the slightest.” - Daeres, in r/askhistorians

While

the flourishing native culture of the palace period dies out, the

great power centers of the Greek world do survive through this

period, as Mycenae and Tiryns

both held their

wealth and power of previous eras. Throughout

the 12th

century BCE Mycenaean culture generally continues albeit

with new cultural influences.

So called “Barbarian

ware” became

popular throughout the Mycenaean world during

this time, and while it was actually a native invention it generally

shows a down-ward trend in elaborate artistry. In addition cremation

becomes slowly more popular, and became the norm in the 8th

century BCE.

|

| A map of some cities destroyed and those which survived the crisis around 1,200 BCE. All of the directional arrows are entirely speculative and should be disregarded |

The

Sub-Minoan and Sub-Mycenaean Period, the 12th

and 11th Centuries BCE

Between

1,200-1,100 BCE, while Mycenaean material culture continued its

political power collapsed. Pottery and decorative styles changed

rapidly while fine craftsmanship and art declined. The citadel at

Mycenae proper remained occupied throughout this period, the Wanax

was able to hold on to some amount of power through the region's

decline. This desperate struggle for control would not last, and by

1,100 BCE the palaces, their titles, and their writing had all died

out on both Crete and Greece.

The only remnants of traditional Mycenaean culture were Achaean settlements on Cyprus and at Al Mina on the Syrian coast. The longest lasting aspect of Mycenaean culture was their dialect of Proto-Greek which was used on Cyprus well into the iron age. While the glory of Minoan culture had faded, elements of Minoan artistic style and pottery continued til around 1,000 BCE. The final place which expressed an identifiable Minoan culture is the refuge settlement of Karfi, on Crete, which continued Minoan traditions until around 1,000 BCE.

|

Even

in areas which suffered better through the collapse, the decline in

artistic quality is evidence. A chlorite vase inscribed with Cypriote

or early Phoenician, 1,100s BCE, Mycenaean Cyprus

|

The only remnants of traditional Mycenaean culture were Achaean settlements on Cyprus and at Al Mina on the Syrian coast. The longest lasting aspect of Mycenaean culture was their dialect of Proto-Greek which was used on Cyprus well into the iron age. While the glory of Minoan culture had faded, elements of Minoan artistic style and pottery continued til around 1,000 BCE. The final place which expressed an identifiable Minoan culture is the refuge settlement of Karfi, on Crete, which continued Minoan traditions until around 1,000 BCE.

|

| A figurine considered a household goddess, found at Karfi during the Sub-Minoan period. It notably includes the Minoan sacred horns |

“While the zenith of Minoan-Mycenaean civilization clearly had passed, the depths of poverty and despair involved in these changes is not a simple matter to assess. Sloppier pottery need not imply poorer people, although it might. Smaller dwellings would suggest lower levels of well-being, but simply less careful construction need not. The magnitude of the populations surviving to retreat away from the coast is difficult to discern from the artifactual remains, and the record of the pull-back is incomplete, so we have little firm, direct evidence of whether the relocations were made by shattered remnants of populations or more or less intact populations.” - Donald W. Jones

Culture

always continues, even as specific identifiers such as Minoan drop

off. There was always a

nobility, even during the dramatic changes between

1,200-1,000 BCE, and

these nobles still

fought in bronze armor and

desired nice pottery. By

1,050

BCE a new style of pottery

became

popular, called Protogeometric. It

was invented in and popularized by Attica, specifically Athens, which

had quickly recovered after the BAC.

After its Attic invention, it

quickly spread to the Peloponnese and Euboea. While

Peloponnese artisans copied the Attic style, Euboean artisans

(centered at its chief city of Lefkandi) developed their own style

using the pendent semicircle. This

Lefkandian style was then spread and copied by Cycladic and

Thessalian potters. Protogeometric

pottery was also spurred on by new developments in technology, such

as using faster wheels

(allowing

potters to make thinner walls),

and using compasses (allowing

perfect circles).

While some iconic forms of

Mycenaean pottery such as the stirrup jar and the squat alabastron

disappear, other forms of pottery survive into the Protogeometric

period, simply taking on a new aesthetic veneer.

|

| A Minoan protogeometric style pot, from the Sub-Minoan period, 1,100-1,000 BCE |

Certain

areas continued more ingrained Mycenaean traditions: Crete and

Thessaly continued building tholos tombs into the early iron age, and

the Argolid continued the LBA burial style of inhumation. Attica not

only championed new styles of pottery, but also the imported iron age

practice of cremation. While

the general economy of farming, weaving, metalworking, and potting

continued throughout these centuries, they were at a much lower

output than previous eras.

Items made in towns in this period were designed mostly for local

use, and painted with local styles. Overall, there is a trend toward

simpler styles in art Protogeometric

art.

|

| A Greek protogeometric style cup with three circles, 1,050-900 BCE |

Argos

and Knossos were continuously occupied during this period, and

many cities were able to rebound quickly such as in Attica, Euboea,

and central Crete. While the elite could recover a semblance of

wealth and power, the lives of the poor generally remained unchanged

as in previous centuries. An

illuminating

example of how a city dealt with the troubles of this era is seen in

the story

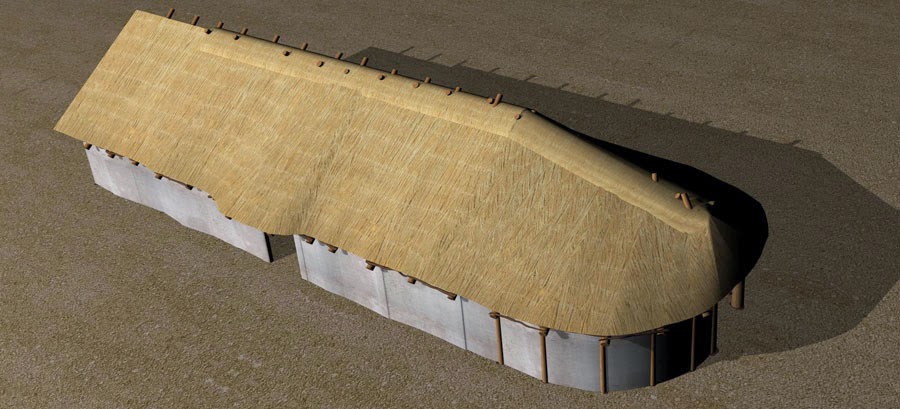

of Nichoria in the Peloponnese. It

was abandoned in 1,075 BCE

but re-emerged 15 years later

as a village. This scaled

down version of the town included 40 families with each having enough

good land for both farming

and cattle grazing. In the

10th

century BCE a building similar to a megaron was built on top of a

ridge overlooking Nichoria, likely inhabited by a chieftain. This

building was made of a similar material to other houses in the town

(mud with a thatched roof) and

while it could also be a

storage or religious building, it

was probably a mini-citadel.

The political heart of the

town had been reformed around

the chieftain's longhouse.

|

| Mycenaean clay sculpture of a temple, ca. 1,100 BCE |

As

society changed

local regions became more independent. Local social structures

re-organized around kinship and oikoi (households),

creating the seeds for the rise of the polis. Most

significantly, the biggest

societal change came

not from the Sea Peoples but from the introduction of iron. From

around 1,050 BCE small iron industries pop up across Greece, as the

technology is imported from Cyprus and the Levant. This

new metal

allowed

a leader to make cheap edged

weapons for their mass of soldiers

unintentionally it

had

democratized the cutting

sword. In previous eras, bronze swords were expensive and reserved

for the elite, that social structure had drastically changed.

Within 150 years (by

900 BCE)

almost all weapons in graves were iron, as

nobility across the Greek world had

universally adopted the

stronger metal in all aspects

of life.

“It takes till around 1050-1000 bce for many of these sites to be re-inhabited, and for the population of Greece to start visibly growing again.” - Daeres, in r/askhistorians

The

Heroon at Lefkandi, and the 10th Century BCE

By

the 10th century BCE most Greeks lived in small

settlements, surrounded by isolated farmsteads. Some settlements had

chieftain houses, such as at Nichoria in the Peloponnese and Lefkandi

in Euboea. These nobles were no longer buried in great tombs, but

cremated and buried with iron weapons. While political society had

become re-organized at a smaller level, some long distance trade

never stopped as Baltic amber continued to be imported from the far

north. The nobles who could afford such exotic items still had

wealth, and still desired exquisite objects.

The

largest building from this era is the chieftain's long house at

Lefkandi, in Euboea. It is called the “Heroon”, and was a long

narrow building 150' long by 30' wide. It included two burial shafts,

one with four horses and the other with two humans. The two people

were a cremated male with iron weapons and an inhumed woman with gold

jewelry. From the scale of the building the chieftain of Lefkandi was

probably the most powerful ruler in Greece at the time, a hypothesis

supported by the spread of Lefkandian pottery and colonists

throughout the Aegean. By 900 BCE the rulers of Lefkandi had even

reestablished trading connections with the Levant, continuing to

aggrandize their political power.

|

| A diagram of the Heroon at Lefkandi, in Euboea |

|

| A reconstruction of the building of the longhouses at Las Camas near Madrid, an early iron age site with a similar structure to the Heroon, phase 1 |

|

| A reconstruction of the building of the longhouses at Las Camas near Madrid, an early iron age site with a similar structure to the Heroon, phase 2 |

|

| A reconstruction of the building of the longhouses at Las Camas near Madrid, an early iron age site with a similar structure to the Heroon, phase 3 |

|

| A cross section of the reconstructed longhouse at Las Camas |

Looking

at the two burials at the Heroon in Lefkand, they both are exquisite.

The man's bones were placed in an imported Cypriote bronze jar which

included hunting scenes on the cast rim. The woman had gold coils in

her hair, gold rings, gold breast plates, and an heirloom necklace.

The necklace, while buried with this woman in the 10th

century BCE, was made 200-300 years previous (around 1,150-1,250 BCE)

either in Mycenaean Cyprus or in the Near East. The woman also

carried an ivory handled dagger. The sacrificed horses had iron bits

in their mouths. The entire structure was most likely created to

house the burial, or had been originally the chieftain's house which

had become his burial plot. Sometime after the burial the building

was destroyed, the site being turned into a general burial plot for

the local nobility. Rich members of Lefkandi were cremated and buried

close to the east end of the building until around 820 BCE.

|

| A terracotta funerary centaur figurine from Lefkandi, Euboea, ca. 900 BCE |

|

| A map of dark age Greece ca. 900 BCE (this picture is actually very large, so save it and zoom in if you need a closer look) |

|

| A reconstruction of EIA (early iron age) Greek warfare |

The

Archaic Period, The 9th Century BCE and Beyond

The

iron age signaled the change and creation of new traditions, such as

with the elite burial and architecture at Lefkandi. Free standing

temples were built, such as a temple to Hera at the summit of the

citadel of Mycenae. Early recorded wars show the development of

serfdom and the emergence of a new political surface to the Greek

world.

“The re-emergence of potent states arguably lies around 800-700 bce. Many areas see lots of strife due to competition between different aristocratic families and clans, who fought over the title of basileus. Writing is re-introduced by the Phoenician script, which is then adapted for the Greeks. But recover they did, even though it took a long time and even though entirely new problems emerged in the wake of the recovery.” - Daeres, in r/askhistorians

Sparta

was first settled around 1,000 BCE, near the larger Mycenaean

survivor of Amyklae. In the first half of the century the Temple to

Apollo was built in Amyklae which incorporated the older shrine to

Hyakinthos (a tumulus of Mycenaean origin which had become a sacred

place). Sometime between 800-750 BCE Sparta conquered Amyklae,

reducing them to a free people (but not Spartan citizens) within the

Spartan Kingdom. Sparta quickly went on to conquer the rest of

Laconia. After locking down their surrounding area they conquered

Messenia after a brutal war between 743-724. This resulted in

reducing the surviving Messenians to serfdom.

|

| A map of the emergent Spartan Kingdom, ca. 700 BCE |

|

| A middle Geometric style pot, 850-760 BCE |

|

| A geometric style pot with female mourner celebrants |

The

old order had changed, ancestral powers like Mycenae and Pylos were

no more. In their place, weaker cities like Athens could hold onto

power by surviving the deluge, cementing their power by inventing and

popularizing new artistic styles. Other weak states like Sparta

reformed itself into a military meritocracy, and had to re-institute

large scale slavery to hold on to power. In 776 BCE the Olympic Games

were establish, these new iron-based Greek cities had begun to

culturally synthesize. Each city-state eventually accepted these

inter-state competitions, along with its internationalist moral codes

such as the recognition of foreign athletes and its enforced cease

fires. It was the beginning of a new Greek culture.

|

| An early archaic Greek helmet from Tarento, Italy |

|

| A reconstruction of that helmet by the Koryvantes reenacting group |

|

| A reconstruction of an archaic hoplite by the Koryvantes group, ca. 800 BCE |

|

| A reconstruction of an archaic hoplite by the Koryvantes group, ca. 800 BCE |

|

| A reconstruction of an archaic hoplite by the Koryvantes group, ca. 800 BCE |

In

the early 8th century a version of the Iliad was written

down by Homer, and as the century progressed a native variant of the

Phoenician alphabet would be adopted by merchants and eventually the

entire literate population, most likely starting in Euboea. This

period would come to be dominated by iron and Phoenician trade,

rather than by bronze and bureaucratic palace scribes.

As the population of cities began to increase once again, some spread their culture by founding colonies in the Aegean and southern Italy. Some of the first cities to found colonies were the ancient rivals of Chalcis and Eretria, both on the island of Euboea. Beginning in the early 700s BCE Chalcis founded a colony in the bay of Naples, and then the city Naxos on Sicily. The rulers of Eretria must have formulated some response, the two would continue to compete viciously each entangling themselves into a network of Greek alliances. These two grand coalitions would come to fight each other by the end of the century in one of the earliest recorded wars, the Lelantine War (710-690 BCE). Chalcis and Eretria were strictly fighting over the fertile plain between their cities, but as each side drew in their allies soon the whole Greek world was at war with itself. Chalcis and its allies (such as Sparta and Corinth) won, destroying Eretria. This helped the entire coalition as Sparta gained more land in the Peloponnese, and the other primary ally Corinth expanded its colonial efforts. By the end of the 8th century BCE, not only had new states emerged from Greece but they began to found colonies once more, wars began to stretch across the whole of the peninsula.

“It is believed that the whole of Homer may have been passed on by oral tradition for several generations before being written down in the 9th century BCE. If this seems unlikely, it is recorded that in January and February 1887, a Croatian minstrel recited from memory a series of lays amounting to twice the combined length of the Iliad and the Odyssey.” - Rodney Castleden

As the population of cities began to increase once again, some spread their culture by founding colonies in the Aegean and southern Italy. Some of the first cities to found colonies were the ancient rivals of Chalcis and Eretria, both on the island of Euboea. Beginning in the early 700s BCE Chalcis founded a colony in the bay of Naples, and then the city Naxos on Sicily. The rulers of Eretria must have formulated some response, the two would continue to compete viciously each entangling themselves into a network of Greek alliances. These two grand coalitions would come to fight each other by the end of the century in one of the earliest recorded wars, the Lelantine War (710-690 BCE). Chalcis and Eretria were strictly fighting over the fertile plain between their cities, but as each side drew in their allies soon the whole Greek world was at war with itself. Chalcis and its allies (such as Sparta and Corinth) won, destroying Eretria. This helped the entire coalition as Sparta gained more land in the Peloponnese, and the other primary ally Corinth expanded its colonial efforts. By the end of the 8th century BCE, not only had new states emerged from Greece but they began to found colonies once more, wars began to stretch across the whole of the peninsula.

While

the politics of the era had changed, more integral aspects of culture

and warfare had remained unchanged. The Geometric Age Greeks, just as

their Mycenaean ancestors, were ruled by slaver elites in competitive

city states. Each city would found and then fight over their

colonies. The dramatic tablets from the 13th century BCE

Hittite Empire show a similar political situation: the mainland and

the colonies were connected by thoroughly intermarried elite families

who rivaled with foreign rulers and mercenaries for power. While many

aspects of culture had changed, the political situation of Greek

cities had not.

|

| An early archaic hoplite reconstruction, without a crested helmet, by the Koryvantes group |

|

| An early archaic hoplite reenactor from the living history association Hetairoi |

|

| A reconstruction of an archaic hoplite |

|

| Another reconstruction of an archaic hoplite |

Other

coastal regions of Greek besides Euboea were interacting with

Mediterranean trade as well, leading to cemeteries throughout the 8th

century BCE becoming richer once again. Burials began to include rich

imports from the near east, Egypt, and Italy. Greek potters began to

export their wares along the old trade routes, to the Levantine coast

and to north central (Villanovan) Italy. A large amount of well made

pottery from the era are found on funerary kraters. An aristocrat

would pay to have a large amphora made and painted with a funerary

scene, it would be placed as if it were their grave stele. The

popularity of this new tradition increased along with its new

painting styles, a native 8th century invention.

Eventually these scenes became more complex and by the end of the

century pottery had become less rigid, more elaborate, and began to

include scenes based on epic poetry.

|

| The Hirschfeld krater, showing a body laying out in prothesis surrounded by mourners, made in the Attic style between 750-700 BCE |

|

| Detail of the Hirschfeld krater |

|

| Detail from the Dipylon krater, a geometric krater also showing prothesis and mourners, 900-700 BCE |

During

this century iron tools and weapons had increasingly better quality,

in conjunction with new supplies of tin and copper which were once

again reaching Greek smithies. Through the 8th century BCE

iron continued to have a humungous impact of peoples' lives. Ever

since its widespread introduction in the 10th century BCE

it had forced society to reform, armies could now more easily be

fielded equipped with powerful weapons. Previously in the bronze age,

swords were only owned by the nobility, but now that swords could be

supplied on a larger scale any noble with enough money could easily

raise a strong force. Society had to adapt to this change and the

simplistic top-down approach of earlier eras could no longer support

strong societies. Local units could hold much more power, and their

cohesion required truly negotiating between factions of equals. While

the rich still controlled the land, power was no longer centralized

in a Wanax, Temple, or 9th century chieftain, but in a

cabal of aristocrats. It was the birth of the Greek polis system.

|

| Late geometric style pyxis with horses on the lid, 760-700 BCE |

|

| A late geometric style pyxis in an Attic style, made ca. 750 BCE |

Hellenistic

and Roman Eras

Mycenae

was still inhabited during this period, and a contingent of Mycenaean

troops fought at Thermopylae and at Plataea against the Persians in

480 and 479 BCE. The city lasted only 11 more years until 468 BCE

when it was conquered by Argos. The Argians expelled the inhabitants,

leaving their truly ancient nemesis plundered and abandoned. Mycenae

was briefly inhabited again during the Hellenistic period, with a

theater being built on the LBA “Tomb of Clytemnestra”.

Surprisingly until the Hellenistic era, some Cypriots such as

Arcadocypriot and Eteocypriot speakers continued to use a script

called the Cypriot Syllabary, directly descended from Linear A.

Eventually during this period Mycenae was finally abandoned, and the

Cypriot Syllabary died out. These two final blows amount to the death

knell for Mycenae's glorious and ancient civilization. The Romans

were still fascinated by the site, which became a tourist attraction.

Its “cyclopean” walls had entered into the Roman mind as a

popular myth, and were mentioned by Pausanias in the 2nd

century CE.

|

| The Cypriot Syllabary, based on Linear A but adopted by Mycenaean colonists on Cyprus in the LBA. It was used until the 4th century BCE |

|

| A Roman coin from Colonia Julia Nobilis Cnossus, near ancient Knossos, showing a labyrinth |

The historic Troy and the

conquered Priam on the other hand, fared well under the lens of time.

Herodotus relates that Persian Emperor Xerxes sacrificed 1,000 oxen

to the Trojan Athena. Alexander the Great made a pilgrimage to the

site as he passed through and (from Arrian) “dedicated

his full armor in the temple, and took down in its place some of the

dedicated arms yet remaining from the Trojan War.”

|

| A reconstruction of the acropolis at the Hellenistic city of Ilion |

|

| Top: Hellenistic Ilium's theater today. Bottom: A reconstruction of Hellenistic Ilion's theater |

Under

the Roman Empire it became a culture-wide focal point of study,

tourism, and identity. As Aeneas came to found Rome, Troy was then

the Romans prehistoric motherland. Various Romans constructed

monuments to their history at the site, Caesar rebuilt the city and

Augustus expanded its chief temple (to Athena). In the mid-4th

century CE Emperor Julian the Apostate noted that fires still burned

in its altars, cult statues of Hector were still anointed with sacred

oil, and that the tomb of Achilles was intact and still venerated.

These rituals were ended with Christianity, the city was devastated

by an earthquake around 500 CE and finally abandoned after the 1,306

CE Ottoman invasion.

|

| A reconstruction of Roman Ilium |

Explaining

the Collapse

“Unless life itself is destroyed in a region, there must always be continuity of some kind.” - Moses Finley

There

is no single factor for the demise of the Mycenaean and Minoan

cultures, but a confluence of different problems which jointly tore

apart their cultural integrity. Many things are suggested, such as:

climate change, earthquakes, population movement, internal conflict,

foreign invasions, a change in weapons technology, or the more

general systems collapse. It should be noted that the destruction is

centered around large cities, and while destruction layers are found

across the entire region, this should not be equated with similar

widespread destruction in rural areas.

“In a single 25 year period spanning the end of the 1200s almost every single palace in Greece is destroyed or abandoned. This is what was interpreted as an invasion/migration for so long, but the simple truth is that 25 years is a long time and there is no reason to attribute a single phenomenon as being responsible for all of this..Some of the great citadels were almost immediately re-inhabited, for example Mycenae and Tiryns were reoccupied almost immediately after the palaces were destroyed...there are several locations where no disturbance is indicated in the material record, most of them lying in Boeotia and nearby regions of Central Greece. There is a growing number of sites that seem to have existed throughout this period of turmoil and afterward.” - Daeres, in r/askhistorians

Climate

Change

The

region Greece through southern Anatolia and Cyprus is prone to

earthquakes, these have been civilization-destroying events having

already occurred on Thera during the preceding few hundred years. The

great earthquake of 1,700 BCE certainly destroyed multiple

temple-palaces (and everything else) on Crete, if that had been

followed by an invasion surely the Minoans could have been wiped out.

While this theory certainly could account for a few cities being

destroyed, it does not account for the 40+ cities destroyed across

the entirety of the near east between 1,200-1,000 BCE. There are no

mass graves, so a widespread plague is also not feasible.

Climate

change is a likely candidate, its symptoms are extended droughts,

heavy floods, drastic temperature changes, and continual bad

harvests. All of those examples are detrimental to the stability of

ruling powers. In the history of China, bad harvests equaled a loss

of legitimacy for the ruling dynasty. In fact, during this period (in

the 11th century BCE) the Shang dynasty was overthrown by

the Zhou dynasty for this precise reason. Severe drought had thrown

the older dynasty into arrears and inspired the Zhou's migration

southwards, leading to conflict and eventually a new dynasty.

In

the Aegean region, a juniper tree's from the period shows

dendrochronological evidence that around 1,200 BCE there were a

series of bad droughts in the region. The Mycenaeans and the

temple-palace structure revolved around redistributing wheat, its

power was centered around its monopolistic control of its

countryside's grain. Wheat rations were used as a form of payment to

the palace-temple's workers. A series of bad harvests would have

ruined the local king's power, depriving the city from paying its

employees.

Around

1,200 BCE Pharaoh Merneptah wrote inscriptions in Karnak mentioning

that he had given grain shipments to the Hittites in order to “keep

alive the land of Hatti.” Part of what allowed Egypt to whether

the storm of the BAC is that they could rely on the Nile's flooding.

Around this time the Hittites reached out to the king of Ugarit (on

the coast of Syria) for help as well, requesting, “You must

furnish them with a large ship and crew and sail 2,000 kor [450 tons]

of grain...[it is a] matter of life or death.” The Hittites

would not be so lucky as the Egyptians.

Warfare

during the Collapse

The

movement of peoples likely played a large role in the BAC collapse,

through foreign invasion and mass migrations. Much of the changed is

considered to be through violence, as during this time most large

cities across the eastern Mediterranean were destroyed. After Pylos

was destroyed, the new invaders did not leave weapons or graves,

suggesting they were raiding. Not every city was destroyed, Athens

survived being razed. Pylian tablet JN 829 shows that coastal cities

took preparations against piracy, and noted “watchers are

guarding the coast.” Another

Pylian tablet is and order

to

take bronze from

the temples to be made into spear points.

Egyptian

and Ugaritic records reference a group they called the “Sea

Peoples” and there are substantiated battles. It is still hard to

distinguish whether these Sea Peoples invasions were a symptom or a

cause of the BAC. There is a fine line between massed forced

migrations and an outright invasion, as the political landscape in

the Mediterranean reshuffled itself it would be hard to distinguish

between the two. In 1,209 Pharaoh Merneptah fought back an invasion

from Libya and “northern lands”, the invaders did not come simply

to conquer, but brought their wives, children, and cattle.

|

| An Egyptian relief showing a Sea Peoples woman pulling a child into a cart during a battle |

It

was a period of large-scale violence as well, the Hittites sacked

Mycenaean Miletus around 1,315 and 1,250 BCE, Troy was sacked

multiple times during this period. The Egyptians fought back the Sea

Peoples three times, although bands of the Sea Peoples called the

Peleset forced the Egyptians to give them land in what is now

Palestine. Etymologically it is possible that the name of the

Philistine tribe is an iron age version of the word Peleset, but it

remains a theory. Some states fully collapsed during this period, the

Hittites were consumed by a civil war, increased piracy (and Sea

Peoples), and an invasion of the Phrygians from Thrace (around

Bulgaria today). A Hittite vassal Hammurabi of Ugarit writes to the

emperor,

“My father, behold, the enemy's ships came; my cities were burned, and they did evil things in my country. Does not my father know that all my troops and chariots are in the land of Hatti, and all my ships are in the land of Lukka...Thus, the country is abandoned to itself. May my father know it: The seven ships of the enemy that came here inflicted much damage upon us.”

The

Hittite emperor replies,

“As for what you have written to me: 'Ships of the enemy have been seen at sea!' Well, you must remain firm. Indeed for your part, where are your troops, your chariots stationed? Are they not stationed near you? No? Behind the enemy, who press upon you? Surround your towns with ramparts. Have your troops and chariots enter there, and await the enemy with great resolution!”

But

Ugarit was burned.

“The intricate, specialized industries such as textiles disappear. Linear B disappears. The palaces are all destroyed or abandoned, and the reach of individual states is greatly reduced. The number of sites with international contacts or dealing in international trade is absolutely decimated; only a handful of islands seem to have still had any international contacts in this period and it took a long time for this to recover. Whilst some places seem to have mostly been undisturbed [Athens], others were; Messenia seems to have been almost totally deserted, the site of Sparta and its nearby area was abandoned and not reoccupied for more than a century. Even after the destruction of the palaces, several sites are damaged by earthquakes, by fire, or deliberately destroyed (although many sites, like that at Lefkandi, rebuilt afterward). It's clear that this was an unstable, violent time in much of Greece.” - Daeres, in r/askhistorians

Another

possible invasion lies in the classical myth of the Dorian people,

who supposedly invaded Greece in prehistory. This explanation is

suspicious, as the invasion is only spoken about in classical sources

and was used as an origination myth by the classical Dorian tribe.

There is nothing archaeologically concrete known about these invading

people, if northern invaders came they did not leave new burials or

pottery. It is more likely that the Dorians later invented this myth

to explain the layout of classical tribes.

While

the foreign invasion narrative is appealing, it is entirely

impossible to assign blame to any of the destroyed cities across the

eastern Mediterranean. It cannot be determined whether a city was

destroyed by the Dorians, Sea Peoples, or fellow countrymen. Some

Mycenaeans and Minoans may have joined the Sea Peoples, conflating

the political outcomes of the two forces. On one hand, the Sea

Peoples are a cause of the continued collapse as they certainly

destroyed cities and destabilized empires; yet on the other hand, the

Sea Peoples were a result of the collapse and preyed on already

weakened empires.

New

Technologies and Tactics

Iron

swords, iron armor, and new tactics exacerbated the decline in older

established armies in the near east. The Naue II sword was introduced

from Europe, it was iron and could cut much better than bronze

swords. Crafting iron swords was easier (as iron was easier to come

across) than bronze, which allowed many more soldiers to have these

devastating melee weapons. The prior bronze swords designed for

piercing was no longer the most effective weapon on the battlefield.

The Mycenaean Warrior Vase was produced in the waning hours of their

civilization, and shows soldiers wearing novel helmets and shields.

Full bronze panoplies, weapons, and chariots had all been signs of

nobility, owned by a small elite. By the archaic era, the yeoman

hoplite became the mainstay of armies and by this period (8th

century BCE) iron weaponry and panoplies had become democratized.

The

central tactical change was through the introduction of these new

tools, now companies of infantry could stand up to massed chariot

charges. This repositioned power to armies who could field large

swathes of infantry, such as the Sea Peoples. These technological

changes were no small part spurred on by the advent and

popularization of iron. By the 1,200s BCE some people did have iron

as the knowedge of iron working slowly left its origin around Urartu

(around Armenia). Those who did have iron could more easily acquire

it (repair their equipment, supply new recruits) than states could

acquire bronze armament.

For

the first time throughout the bronze age, large regiments of infantry

could be fielded with powerful weapons and defeat the chariot. The

chariot had been powerful throughout the early bronze age, first

effectively used on a large scale by Sumerians with their donkey led

war wagon. Those days had finally concluded. In the 10th

century BCE the first regiments of horsemen were employed by the

Assyrians, and iron armored cavalry regiments were continuously used

until the 20th century CE. It should be noted that the Sea

Peoples, disregarding their iron weaponry, were fierce fighters. An

elite from among the Sherden tribe were selected by the Egyptian

Pharaoh to become his personal body guard, a tradition begun by

Ramesses II after his victory over the tribe in 1,277 BCE.

Systems

Collapse

A

more interesting and powerful idea about the BAC is called systems

collapse. This theory suggests that the destruction of the carefully

curated shipping lines and commercial networks between large city

states throughout the region in the 13th century BCE was

the primary cause of decline. This was only further propelled by

foreign invasions of Sea Peoples around the end of the century and

into the early 12th century. Commercial operations

required safety, and particularly the prosperity of coastal regions

(such as the Levant or the Aegean) had become dependent on external

markets for their surplus luxury goods. The grand Mycenaean palaces

and their bureaucracies were heavily dependent on the steady

production of their peripheries, carefully recorded by their scribes.

If surplus shipments stopped, or if a king was deposed, or if pirates

attempted to sack your city, everything would be thrown into chaos. A

few of these events happening at the same time could ruin a city.

“The availability of enough tin to produce...weapons grade bronze must have exercised the minds of the Great King in Hattusa and the Pharaoh in Thebes in the same way that supplying gasoline to the American SUV driver at reasonable cost preoccupies an American President today.” - Carol Bell

The

bronze based military empires of the near east and Aegean required

long distance trade with the Badakhshan region of Afghanistan for

tin. The quantities of tin required to make bronze forced near

eastern rulers to rely on foreign imports to supply their armies. As

can be expected, this foundation for military power is very unstable.

The area around Afghanistan also suffered political crises during

this period, and if a slight dip in trade turned into a break in

trade each kingdom was stranded and weak. While the Assyrians,

Babylonians, and Elamites would have trouble managing this crisis

within their extended kingdoms, a single Wanax in Mycenae with only

familial connections to a few other cities would have been utterly

overwhelmed. The question as to what exactly caused the BAC is still

by no means settled, with many explanations only covering partial

areas or with cursory extent. The true extent of the collapse is a

continued question of debate within the historical community.

Aspects

of Mycenaean Culture which Survived the BAC

Besides

the Cypriot Syllabary, other specific

aspects of Mycenaean culture survived into the classical period. The

position of the Wanax was classically redefined

as a Basileus,

which is a

cognate of qasirewija.

In classical society the

highest aristocrats formed a council of elders called a Gerousia,

possibly a cognate of the Linear B term kerosija.

Mycenaean Damo is

a cognate to the classical term Demos,

which served as the political base of the classical system. The

classical term polis does

not arise, except in the personal name Potorijo (later

spelled as Ptolis or

Polis).

The township worshiping city gods of the classical era is similar to the Damo giving tribute to Poteidan. Shrines dedicated to specific gods also survived the collapse, many rural shrines could survive and even some urban ones did too. One such example is the urban shrine to the Mycenaean god Hyacinthos at Amyklae, which was only destroyed between 800-750 BCE when it was incorporated into a temple to Apollo. The continuance of rural shrines predated the rise of the polis and eventually, as cities became politically and religiously most powerful than the countryside once again (in the 8th century BCE), all rural shrines were eventually incorporated into their nearest polis.

The township worshiping city gods of the classical era is similar to the Damo giving tribute to Poteidan. Shrines dedicated to specific gods also survived the collapse, many rural shrines could survive and even some urban ones did too. One such example is the urban shrine to the Mycenaean god Hyacinthos at Amyklae, which was only destroyed between 800-750 BCE when it was incorporated into a temple to Apollo. The continuance of rural shrines predated the rise of the polis and eventually, as cities became politically and religiously most powerful than the countryside once again (in the 8th century BCE), all rural shrines were eventually incorporated into their nearest polis.

References

The

Lelantine

War http://www.ancientgreekbattles.net/Pages/75080_Lelantine_War.htm

Geometric

and Protogeometric Pottery http://bit.ly/1x8eHPq

Protogeometric

Pottery http://www2.ocn.ne.jp/~greekart/vase/h_proto_e.html#6

LM

and Sub-Minoan Crete, by Donald W. Jones http://bit.ly/1x8eGep

Early

Archaic Hoplite http://bit.ly/1y3UrCy

Bronze

Age Collapse in Greece, by

Daeres http://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorians/comments/1dslor/

Ancient

Greek thought about the BAC

by

oudysseos http://bit.ly/1IPKD0K

Collapse

of Palatial Society, Guy D,

Middleton http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/2900/

BAC

Lecture, by Ethan

Spanier https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9cPGBeH8PbY

Climate

Change in the Shang Dynasty (see China) http://bit.ly/1MfdzCI

Mycenaean

and Archaic Hoplite, by

Koryvantes http://koryvantesstudies.org/studies-in-english-language/page202-2/

Herodotus

and the

Eteocretans https://camws.org/meeting/2010/program/abstracts/03A2.West.pdf

%2Bat%2BMinoan%2BKommos%2C%2B4m%2Bhigh%2Band%2B40m%2Blong%2C%2Bheld%2Bfrags%2Bof%2Bshort%2Bnecked%2Bamphoras%2C%2Bmaybe%2Bheld%2Bships%2C%2Bmade%2Bca%2B1360%2Bbce.jpg)

I admire the valuable information you offer in your articles. I will bookmark your blog and have my children check up here often. I am quite sure they will learn lots of new stuff here than anybody else! Real Human Skull for Sale

ReplyDeleteI'm no longer positive where you are getting your information, however good topic Indian black granite exporter

ReplyDeleteWow, such a huge collection of Bronze age material, there is one more topic you would like to read about Indian Black Granite

ReplyDeleteGreat blog article about this topic,I have been lately in your blog once or twice now.I just wanted to say hi and show my thanks for the information provided. online organic grocery shopping

ReplyDeleteI am bookmarking this page, in the future I might try to write a book to go along with my blog, but I will see. Looking forward for more post with useful tips and ideas. Trimethylsilyl

ReplyDelete